https://ph.trip.com/moments/destination-macau-39/

2025 Macau Travel Guide: Must-see attractions, popular food, hotels, transportation routes (updated in October)

Macau blends Portuguese charm with Chinese energy in one dazzling hub. Stroll pastel-hued plazas and lantern-lit temples, then step into the glow of Asia's grandest casinos. Savor iconic street eats like egg tarts and pork buns while exploring UNESCO World Heritage sites and vibrant markets. Let our local guide craft your perfect trip—discover Macau with confidence!

Macau Today's weather

Clear 23-32℃

Trending in Macau

Popular Attraction in Macau

Ruins of Saint Paul's

(550)Rua Do Cunha

(317)The Londoner

(301)Macau Tower

(183)The Venetian Macao

(153)A-Ma Temple

(133)Macau Eiffel Tower

(129)The Parisian Macao

(113)Studio City Macau

(112)teamLab SuperNature Macao

(99)City of Dreams

(90)Studio City Water Park

(60)Macao Grand Prix Museum

(54)Macao Science Center

(51)SkyCab

(42)Golden Reel Figure-8 Ferris Wheel

(32)House of Dancing Water

(17)Macau Venetian Gondola Experience

(17)Sands Resort Macau

(8)Macao Open Top Bus

(1)All Trip Moments about Macau

Macau day trip itinerary🇲🇴

Traveling in Hong Kong 🇭🇰 At my mother's request, we went on a one-day tour of Macau! Macau is divided into the Plaza Area, a famous World Heritage Site, and the Taipa District, home to many casino hotels. And there are tons of free shuttle buses! This time, we'll introduce a route that makes full use of this free shuttle bus. ✨ It was a fun trip even in a single day, so Please take a look.♡.* ⚘ 〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰 ▶︎ Adult travel information here 《@moco_trip_》 〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰〰 ♡ Save this for future reference.✍🏻 #Macau #MacauTrip #MacauFood #HongKongTrip #Travel #InternationalTravel #MacauSightseeing #InternationalFood #DayTrip #TravelGirl #AdultGirlsTrip #TravelGirl #FamilyTrip #QuickTrip #TravelDiary #MacauTravel #TravelMemories #GourmetTravel #OverseasTravelGuide #ZeroYenTravel2025Autumnmoco_trip_5Grand Prix museum Macau

The Grand Prix Museum in Macau is a thrilling family stop. Kids and adults are fascinated by real race cars bikes, simulators, and interactive exhibits, while parents enjoy the history of motorsport. It’s an exciting blend of speed, culture, and hands-on fun that brings Macau’s racing spirit to life. It displays the best drivers in Formula 1 history and and it teaches about cars and bikes. #adventuremomentsVLWJTW5🇲🇴Macau Peninsula. Highly value-for-money five-star hotel🏛️

🇲🇴 Macau Peninsula. High value for money five-star hotel 🏛️ Noble and elegant decoration. Authentic Portuguese cuisine. Close to photo spots 🩷💛 I quite like the colorful Portuguese-style buildings on the Macau Peninsula⛪️ Every time I get beautiful photos ~ this time I chose to stay at "#MacauRoyalHotel" It is the first five-star hotel in Macau, the service and decoration maintain five-star standards☺️ The location is super convenient, you can walk to Tai Samba, Crazy Hall area I personally recommend you to go to the crazy hall area, you can take very cool photos 💚🧡 and there are hipster shops 🍃 🍾Hotel stay experience Executive Suite Classic and elegant décor, crystal lights, marble bathroom The big bed and sofa seat are beautiful to take pictures 🥰 There are also champagne🥂 Portuguese cookie snacks, fruit for us to enjoy, very sweet!! We also went to the indoor constant warm water pool and gym 🏋🏻♀️ The swimming pool has a skylight to let the sun come in. It's very comfortable! Relax so often in a very elegant environment ☁️ This price is really great value!! 🫖Royal Lounge of Royal Capital Hotel Some packages are suites with afternoon tea packages🫖 I want high tea la ~ the lobby lounge environment is open and comfortable 😌 The afternoon tea has 4 desserts 🍮 and 5 savory dishes, which taste excellent I especially like the rich and smooth chocolate cake! Additional strawberry 🍓 Napoleon, pastry and fresh fruit sweet and sour combination 👍🏼 Then order the crab meat croissant for lunch 🥐 crispy on the outside and tender on the inside, the crab meat is delicious! There will also be supper and live band at night, so you can have a drink🥃 🍴Flower Road Portuguese Restaurant The chef 🧑🏻🍳 is Portuguese and can enjoy authentic Portuguese cuisine You can arrive a little early for dinner, you will see the Macau street view and sunset🌇 is very beautiful!! The food is exquisitely presented, and I recommend the #Malandisha Grilled Eye Steak The meat is tender and fresh, pan-fried just right The fried horseradish potato strips are crispy and I eat them one bite after another ~ ha The crab meat stewed bread is also amazing. The crab meat is tender and juicy Thinly sliced octopus 🐙 Fresh and delicious, smooth and rich seafood flavor 😋 Highly recommended If you/a friend plan to go to Macau 🇲🇴 search this hotel, you will find that it is really great value 🥰🥰 @hotelroyalmacau Ig: @serena.taoo 。 。 #Macau #MacauTravel #MacauHotel #hotel #macau #macaufood #macauhotel #fivestarhotel #September Good Places 2025Serena Tao4Immersive Luxury Hotel Experience

📍70s Escape → Head to Macau and stay at the Sofitel Macau at Ponte 16. The hotel exudes grandeur and is conveniently located near the Ruins of St. Paul's and the old town of Macau, making it an ideal base for exploring this vibrant city. Additionally, the hotel offers direct shuttle bus services. The rooms are comfortable and fully meet the five-star standards of Sofitel hotels. The hotel is imbued with French romanticism, and the bathroom amenities are from the Lavin brand, showcasing ultimate luxury. What stands out the most is the service provided by the hotel staff. They are always smiling and ready to cater to your every need. Whether it's the club or the gym, the service is top-notch. Kudos to them! Sofitel Macau at Ponte 1670後出走3Enjoy the best Portuguese cuisine in Macau 😋

📍70s out → Today to Macau, naturally to taste Portuguese-style meals ~ There is something different about the Portuguese restaurant in Macau. The decoration is romantic enough! White walls with blue windows, many high-quality photo spots, even the vivid green mosaic tiles on the wall have a strong Portuguese feel, you may think you have flown to Lisbon! 🍖Recommend the must-eat Portuguese roast suckling pig, the skin is really crispy to make a sound, the teeth still carry meat flavor; grilled sardines with potatoes is just as Portuguese hometown flavor ~ dessert must come a classic soufflé, surprise is that a special person personally distributed soufflé to customers, service courteous to do not have to move your own hands. The waiters in the restaurant are very attentive. They can replenish their tea and water at any time, so they don't feel thirsty. We were a group of 10, the atmosphere is chill, everyone ate to great satisfaction, sincerely recommend to a group of friends or family gathering to try! Restaurant INFO: 📍Rooster Portuguese cuisine Address: 10AB, Bai Bao Building, No. 10, Oriental Slope Lane, Macau 🍷Good atmosphere and not expensive, such great Portuguese food, really a must-have for a trip to Macau! #tripmoments #Macau itinerary #Macau Food #Macau Family Good Places #Macau Portuguese Cuisine70後出走3Macau Grand Lisboa Hotel Buffet: Eat delicious food and take beautiful photos for the internet 😋

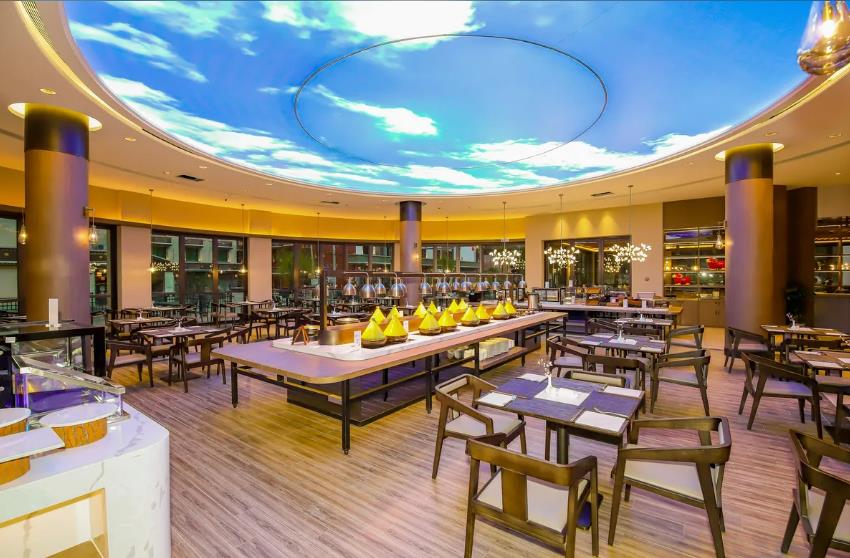

In recent years, Macau hotels have become increasingly beautiful, with interior and exterior design becoming increasingly more impressive! Next time, the most attractive Macau hotels I'd like to stay at would definitely be the Grand Lisboa or The Londoner ✔️ Although we only had a three-day, two-night itinerary with an early morning departure and a late evening return, we didn't miss out on the all-you-can-eat lunch at The Grand Buffet at Grand Lisboa and the local snacks on Guanye Street. 😋 Booking in advance happened to coincide with a 18% discount for two people, making it cheaper than buying in person. We recommend booking buffets in advance using the app to get a discounted price! ️ We two foodies ate from 12:00 PM to around 3:00 PM and were incredibly satisfied 🤣 The most surprising thing was that after our meal, we went to the outdoor Grand Lisboa Gardens, the "Greenery Garden," to walk around and take photos. It was truly stunning. The garden is huge, and the theme this time was Alice. The playing card seats and standees were so cute and creative, perfect for photos. In the center, there's a giant dome and a fountain, creating a truly romantic garden atmosphere. The Baroque architecture made it feel like we were transported to Europe! My husband's birthday is in May, so we even made a homemade cake together 🩷 romantic💕 My husband, who loves seafood, of course devoured all sorts of seafood – it was well worth the price of admission 👍 📍Address: Rua do Shoten, Cotai, Macau 🏖️Atmosphere/Facilities: A true five-star resort. Besides the delicious food at The Grand Buffet, the lush gardens are incredibly photogenic, perfect for Instagram and Facebook posts. 💕And best of all, it's close to the airport, with a free shuttle bus for super convenient access. It's one of Macau's top choices for luxury accommodations, entertainment, shopping, and shopping! #GrandLisboaHotel #GrandLisboaBuffetHill #Macau #Macau #buffet #foodblogger #travel #travelholic #100WaysToTravel跟著熊熊一起去旅行5Enjoy breakfast at the London Tower in Macau

#September Good Places 2025 Conrad Macau is located in Londoner, Taipa and can be reached by free Londoner shuttle from the airport or pier. I started to feel the care of the hotel from the moment I checked in, the rooms were clean and quiet, the service was very good and I will want to stay again on my next trip. The Corner room is a small suite with very comfortable bedding. The rooms are even more amazing, the spacious space is tastefully furnished. A good night's sleep is not a dream. The panoramic window has a wide view, or overlooking the night of the city of Cotai. The room comes with two bear dolls and ducklings to take away, toiletries are using Byredo, which is very comfortable to wash. Downstairs you can take shuttle buses, taxis, buses, and a number of well-known restaurants. Walking distance to Venetian for gondola boat rides, Wynn Cable Car for water dances, Eiffel Tower...etc. The best thing is the room service breakfast, the beautiful scenery is everythingkkcclau5Sharing my experience of traveling in Maque Station 😆

📍70s left → This time take the Macau Light Rail. And Ma Kok Station is almost two years old ~🚄 Some of the 10 shops in the station have already been rented out and are already open! I wonder if you have noticed it? 👀 Just get on the train at Ma Kok Light Rail Station and wander around the shops in the station. I found that these two are really something special. It's worth walking around and discovering new things! Address: Ma Kak Light Rail Station, Ma Kak Shuttle Station, Macau Opening hours: Depending on each shop, we recommend you to check before going ~🙌 Take a leisurely trip, take the light rail while shopping, experience the new landmark and new atmosphere of Macau😎✌️ #Macau Trip #MacauLightRail #MacauTrip #MacauTravel #MaGaoStation #MaGaoLightRail70後出走3Macau Barracks Station Transportation Guide

📍70s → Today arrived at Macau Ma Gao Station (Portuguese: Estação da Barra, English: Barra Station) is the terminus of the Macau Light Rail Taipa Line, located in the southwest of the Macau Peninsula, Sai Wan Lake View Road, really super convenient! 🚝✨ This underground station is beautifully designed and connected to many popular places in Macau. And with the latest routing design of the Macau Peninsula section, it is so easy to travel by light rail, no need to be afraid of traffic jams! Address: Lakeview Avenue, Sai Wan (exit of Ma Kok Station is nearby!) Opening hours: According to the official website of Macau Light Rail, there are buses from 6:30 am to 11:30 pm basically every day It's really convenient to start from Ma Kok Station. It's really convenient to visit Macau. Mark this transportation tip! 🔗🗺️ #tripmoments #MacauTrip #tripmoments #MacauGood Places #MacauLightRail70後出走3Macau's Fulong New Street Food Guide

📍70s Escape → Today's Macau Adventure The wontons at Cheong Kei Noodle House are truly packed with flavor, with shrimp that is incredibly fresh and sweet! A must-try is their signature Shrimp Roe Tossed Noodles, where the shrimp roe generously covers the entire bowl. Mix it well, and every bite is rich, savory, and satisfying. You'll leave feeling completely content! 😋 Another highlight is their Macau-style snack—the Crispy Fish Ball. It's a combination of fried dace fish balls and fried wontons, coated with crispy rice. The outer layer is crunchy, while the inside is delightfully bouncy. The dace fish balls are boneless, perfect for those who don't want the hassle of picking out bones! Pair it with their special dipping sauce for an even better taste. 😍 Address: No. 68, Fulong New Street, Xinma Road, Macau If you're heading to Fulong New Street in Macau, make sure to gather your friends and enjoy a meal at Cheong Kei Noodle House! 🦐🍜70後出走3🎀Holding delicious food in hand, the atmosphere of Macau is instantly captured

📍70s left → Today arrived at Macau Guan Ye Street 📍Mong Kee Coffee in Guan Ye Street is a must try! 😋 The signature curry fishballs here are super authentic, spicy and fragrant! 🐷Pork chop bun is a must-eat in life, the crust bread is so crispy that it falls off when you bite it, the pork chop texture inside is Q bouncy and Juicy, sooo good! 🎀 Also, you can't miss Mong Kee's signature milk tea, super rich milk flavor, immediately refreshed after drinking! 📍 Mong Kee Coffee: 1 Guan Ye Street After eating, walk around Guan Ye Street to feel the local Macau style. It is suitable for a slow walk with friends. The more you eat, the happier you will be! 🫶 #tripmoments #Macau Trip #Guan Ye Street Food #Coffee Shop #Milk Tea Control #Pork Chop Bao70後出走3A hotel that looks like an amusement park

#9月好地方2025 Stepping into the Star Club Hotel at Studio City Macau 🏨 is like stepping into the Toy Story universe! Iconic Buzz Lightyear figures are everywhere, from the lobby to the hallways, offering a surprising twist. The interstellar hero strikes a variety of stylish poses, inviting guests to take photos. Every corner is a unique photo-op: some recreate classic movie scenes, others are brimming with futuristic sci-fi, reminiscent of a vibrant amusement park. Children and adults alike couldn't help but exclaim in wonder, busy creating joyful memories with Buzz Lightyear. This isn't just a hotel; it's a magical journey filled with childlike fun and imagination!牛蛙與節瓜3Macau | Lord Stow’s at the Venetian: A Visit: Crossing the Grand Canal for a Fresh Caramel Pudding 🥧✨

#September Good Places 2025 In the Grand Canal Shopping Center of the Venetian Macau, Lord Stow’s Bakery brings the “freshly baked” sense of time to the counter: the outer layer of mille-feuille pastry clicks, the inner core is a slightly trembling milk and egg pudding, holding the box of goose yellow cardboard in hand, shopping seems to have more destination. Background Story and Development History | How a Portuguese egg tart became a business card for Macau’s taste In 1989, British baker Andrew Stow opened Lord Stow’s Bakery in Coloane. He tweaked the concept of Portuguese Pastéis de Nata into a version closer to Chinese tastes—crispier pastry, smoother milk and egg filling, and toasted caramel spots on the surface. From the Rowan main shop all the way to the peninsula, Cotai, there is the Venetian shop such as "travelers easiest to buy by the way" branch. This little dim sum was accidentally written into the city's love history: Andrew's early cooperation and separation allowed Macau to have another "Margaret"-based egg tart branch at the same time. Both factions have their supporters, but "eat freshly grilled and eaten hot" is the consensus of everyone. ⸻ Actual Interview Route | The 20 minutes I bought egg tarts at the Venetian 1. Find a shop: Follow the directions to the Grand Canal Shopping Center to the San Marco Square area, where you will see a small wall of goose yellow cardboard boxes stacked in the distance, a shelf oven behind glass. 2. Order: I usually directly say "six original flavors", plus one while walking to eat; if the day has custard, butterfly pastry to pick two pieces. 3. Time out of the oven: Whole point or half point is often the peak of a new plate; the shopkeeper will remind you to be careful of scalding. The entrance is most charming when the heat is 90 minutes. 4. Eat while walking: the first bite first listen to the sound - the pastry "click" of crispness, then the milk and caramel aroma spread upward; walk to the arcade to see the "sky canopy", feel like a tourist and like people in the album. ⸻ Palate notes • Original egg tart: surface burnt spots are evenly distributed, the center slightly shakes; the outer ring of mille-feuille is a dry flaky pastry, not oily soft type; the filling milk-egg ratio is not too sweet, most like pudding when warm. • Custard/Butterfly Pastry: The custard is layered, the crust is slightly crispy; • Packaging: Yellow box carton has ventilation holes, within 2–3 hours the flavor is still good; ⸻ 5 Q&As you may be curious about Q1. How long does it take to queue? 45-60 minutes is not unusual on weekends/even holidays;5–10 minutes during non-dining hours on weekdays. Q2.Can I bring it on board? Purchase on the day of departure is the safest; don't squeeze your handbag, go home and bake again. Q3.Are there any different flavors? The mainstay is original; the store occasionally sees other western pastries, but the egg tart is the main stage. Q4.When is the best time to buy? Whole point, half o'clock easily encountered out of the oven; before nine o'clock in the evening there will be a wave. Q5.Will it be too sweet? The sweetness of Andrew's is medium to low, with caramel aroma arriving first and sweetness collected cleanly. ⸻ Reason for recommendation 1. The sense of time of fresh baking: you can see the oven, hear the pastry peeling. 2. Super convenient location: In the Venetian shopping center, it is convenient to stroll, watch the show, and go back to the room. 3. Classic taste: crispy outside and smooth inside, burnt spots fragrant but not bitter, hot eat invincible. 4. Packaging is easy to carry: yellow box is highly recognizable, suitable for gift giving; there are 6/12 into the choice. 5. Friendly price: a single tens of MOP, stable CP value. 6. Rainy day preparation: all indoor shopping mall, bad weather can also be arranged. ⸻ Practical Information (Slack Guide) •Address: Golden Light Avenue Connecting Highway, Cotai, Macau | Venetian Macau Resort / Grand Canal Shopping Center (near St. Mark’s Square) • Transportation: Take the hotel’s free shuttle bus to the Venetian and walk for 3–8 minutes according to the mall guide directions. •Operation: Subject to mall;high frequency of roasting in the afternoon to evening. •Price: around MOP$13–15 per tablet;6-pack/12-pack boxed (subject to on-site marking). • Payments: Swipe/mobile payments and cash can be used in parallel; •Reserve fresh: 6–8 hours at room temperature, best eaten on the day;rebake please use oven or air fry. ⸻ Surroundings/Accommodation (Turn your sense of taste into an itinerary) • Venetian Canal & Artificial “Blue Sky”: Find a chair by the arcade with an egg tart and watch the boatman sing while you eat. • The Parisian/Cinema City Macau: Accessible by footbridge; • Accommodation: Staying in a Venetian or Parisian, returning to your room at night to bake is the highest perk for egg tart fans. ⸻ Review content (with address) • Store name: Lord Stow’s Bakery—The Venetian Macau •Address: Venetian Macao Grand Canal Shopping Centre, Golden Light Avenue Connecting Highway, Cotai, Macau (near St. Mark’s Square area) • Order: Original Egg Tart 6pcs + Crocus/Butterfly Pastry. • Comments: The outer layer is crisp, fragrant and not greasy; ⸻ Take photos (mobile phone can post videos)📸 1. 45° depression angle to shoot the "triangular composition" of three egg tarts, the most beautiful focal spots. 2. Natural light against the window makes the pudding layer shine; placemat or yellow box as the foreground. 3. Oven perspective: Put the oven plate and yellow box in the same frame, "just baked" story sense full. 4. Hold in hand: Focus up close to the pastry layer, revealing a little trademark as well. Real advice (pit avoidance/takeaway/baked back)💡 • Avoid pits: do not shoot for a long time in front of the counter during peak hours, buy first and shoot later; • Take-out back to hotel: Place the box on the upper level of your luggage to avoid squeezing and return to your room to warm up in the oven or air frying; • Weather: The pastry drops quickly when the humidity is high;1–2 pieces are recommended to be eaten within 30 minutes. • Sharing ratio: 6 pieces for 2 people is just right; 12 pieces for 4 people can eat "hot + re-roasted" two tastes. • Insurance stomach: If you are not sweet, taking black coffee/sugar-free tea will push the caramel aroma cleaner. • Children: Fresh from the oven very hot, please be careful of the filling; Andrew's Egg Tart Venetian | Venetian Macau | Grand Canal Shopping Centre | Parisian Macau | Studio City #MacauFood #AndrewEggTart #LordStows #Venetian #GrandCanalShoppingCenter #MacauDessert #MacauEats #EggTartConnoisseur #CotaiCity #MacauTravel 🥧🛶Heinrich85883Made a special trip to Macau just for these 18 photos! Attached is the flight position guide

Macau is the beautiful blend of Chinese and Western cultures. Every old building tells a romantic story. At the crossroads, passersby shuttle around the Ruins of St. Paul's. The glittering Grand Lisboa reflects Macau’s rustic luxury. ❶ Ruins of St. Paul's p1: Love Lane p2 p3: Low angle on the right side of the Ruins of St. Paul's to avoid crowds p4: Walk to the big tree on the right side of the Ruins of St. Paul's ❷ Fisherman’s Wharf The “Roman Colosseum” is a place 99% of people overlook! Worth visiting and great for photos. p5 p6: Circular corridor of the Colosseum p7: Symmetrical shots on the square p8: Enter through the big white gate, take the first road on the left inside ❸ The Londoner’s Big Ben area, New District check-in spot p9: Third floor of the skybridge outside The Londoner, photographer shoots upward from under the skybridge p10 p16: Shot of the clock from the Four Seasons hotel corridor p11: Doorway on the road from Parisian Garden to The Londoner p12: Lawn in Parisian Garden (there’s a collection of 9 Eiffel Tower photo spots in the Macau collection) p13: From Parisian Garden to Macau Sheraton p14: Corridor from Four Seasons to The Venetian p17: Parisian’s illuminated arch at night ❹ Guia Lighthouse p15: Same frame shot with Grand Lisboa Hotel Macau Highlights Two-Day Tour Route Day 1: Macau Peninsula Old Town 📍 Explore around Guia Lighthouse, check in at the National Geographic photo spot Arrive in Macau - Fisherman’s Wharf - Grand Lisboa & Old Lisboa - Ruins of St. Paul's - Fortaleza do Monte - Rua da Guia - Guia Lighthouse - Check in at Galaxy Macau - Evening dining and strolling Day 2: Macau New District 📍 The Parisian - Eiffel Tower - Parisian Garden - Four Seasons luxury shops - The Venetian - The Londoner - City of Dreams - Wynn Palace music fountain This area is full of luxury hotels and very photogenic Tips: 🚗 For travel between Old Town and New District, you can take the free shuttle buses provided by the hotels! It’s recommended to take the shuttle between Wynn Palace and Wynn Macau! You can walk to Ruins of St. Paul's and Grand Lisboa easily! Very convenient! If you want to take a taxi, you can first take the hotel shuttle to Old Town/New District, which is the most cost-effective! Autumn citywalk mapMartin Johnathan Jon3Macau's Guanye Street surprise! Instantly discover a Portuguese restaurant in Lisbon 🇵🇹

#September Good Places 2025 Pushing the door open was directly startled! The entire floor-to-ceiling windows allow sunlight to flow in without reservation, the restaurant is transparent and warm, the light is so good that there is no need to adjust the filter ~ When you look up, you will see the historical buildings of the old town of Taipa. The retro feeling is full, and you will think you are standing on the street corner of Lisbon in a trance! You can also enjoy the scenery of the old city while eating Portuguese cuisine. The experience is great If you want to find atmospheric Portuguese cuisine in Macau, this restaurant is really good for taking pictures or tasting delicious food. Don’t miss it when you stroll through Guanye Street!Krittkin4First time in Macau, highly recommend following this route

Just landed in Macau and I got it All those 100-page guides I made before were wasted This personally tested itinerary is the right way to explore Macau, avoiding all the pitfalls in dining, accommodation, and transportation. No need to flip through notes, just follow along and enjoy💃 · 📍Location: Grand Lisboa Macau Integrated Resort 🚘Transportation: From Gongbei/Hengqin Port, take the free hotel shuttle bus directly to the resort, super convenient for getting around; · 🚶♂️About the attractions 1️⃣ Golden Street (Jinbi Fang) Golden Street is a food and cultural landmark at the west end of Macau’s Senado Square. Sen Zai Gas Station and Crab Roe Hotpot attract many handsome guys and beautiful girls to taste and check in. Many nearby attractions are within walking distance, including Senado Square, St. Dominic’s Church, and the Ruins of St. Paul’s, iconic Macau landmarks; 2️⃣ Green Oasis Garden Located on the 3rd floor of Grand Lisboa, compared to the crowded Ruins of St. Paul’s, this spot is more comfortable for photos, with fewer people and beautiful scenery, easily capturing the Alice in Wonderland garden vibe; 3️⃣ Grand Lisboa Macau Art and Culture Museum "Lisboa · Macau Stories" Located on the 2nd floor of Grand Lisboa, advance reservation via the mini program is required. The exhibition opens with a five-minute 180-degree panoramic film showcasing over 500 years of Macau’s cultural fusion between East and West. The main exhibition features treasures like gold leaf wood-carved dragon boats and Mazu deity robes. The journey connects Macau’s past, present, and future through eight major landmarks, including the Kun Iam Temple, Grand Lisboa Hotel, and Teatro Dom Pedro V. The Treasure Pavilion also displays Chinese imperial treasures such as the Kangxi Emperor’s throne from the Qing Palace; 4️⃣ cdf Grand Lisboa Store and NY8 New Yaohan How can you come to Macau without shopping? The cdf duty-free store and NY8 New Yaohan inside Grand Lisboa offer a one-stop shop for big brand cosmetics, cultural and creative products, trendy clothing, toys, snacks, and more—fun and great for browsing; 5️⃣ Grand Lisboa Lobby East and West Wing Art Corridors The artworks in the lobby complement the European luxury decor perfectly. It’s ideal to wear European vintage-style clothing here for photos that capture a noble aristocratic vibe; · 🍝 Food Recommendations “Congee & Noodle House” at the East Gate entrance of Grand Lisboa has a naturally elegant style, with beige decor accented by warm wood elements, creating a cozy and relaxed atmosphere under soft lighting. Recommended signature noodles include Yi Gen Mian, knife-cut noodles, and Lanzhou hand-pulled noodles, with a texture similar to udon but chewier. Also worth trying are fresh meat soup dumplings, lemon pineapple char siu puff pastries, and Portuguese sauce fresh bamboo rolls. Don’t miss the nourishing fresh Macau water crab congee, each bite tantalizing the taste buds. The eight-treasure tea is exceptional, and there are tea art performances at specific times; · 🍯 Hidden Food Gems When tired, you can go to the ground floor casino in Grand Lisboa where free milk tea and various snacks are available with unlimited refills—so delightful;Nora.Brooks^7137Reading Macau at the European-style stone wall: Ruins of St. Paul's

Starting from Senado Square and following the crowd, stone steps unfold beneath your feet, and the sky resembles a sail opened by the sea breeze. As you look up, the solitary stone wall stands amidst the shadows of clouds and green trees—this is Macau's most iconic landmark: the Ruins of St. Paul's. Its presence is as striking as an open, thick book, with a cover scorched by fire, yet still compelling enough to make you want to read on. The Ruins of St. Paul's is actually part of the remains of the "Church of St. Paul." The original church, named "Mater Dei" (Mother of God), was part of the Jesuit architectural complex along with the adjacent St. Paul's College, built between 1602 and 1640. The college was established earlier, in 1594, by Jesuit missionary Alessandro Valignano. Together with the nearby Mount Fortress, the church and college formed the visual center of Macau's "citadel," witnessing the early spread of religion and knowledge in this port city. This architectural ensemble faced numerous challenges: it endured fires in the 17th century, with the most devastating being the fire during a typhoon night in 1835, which consumed the entire church, leaving only the façade and the long stone steps we see today. From the square below, there are 68 granite steps leading up; each step feels like walking through a history interrupted by flames. Up close, the façade stands 25.5 meters tall and about 23 meters wide, designed in a Baroque-Mannerist style and divided into five levels. The lower level is supported by columns and arches, the middle level features niches and statues of saints, and the upper levels gradually taper off. The stone surface is rich in details: the Jesuit emblem "IHS," Portuguese ships, chrysanthemums and lotuses, mythological and biblical scenes, and Chinese-style stone lions on both sides—Eastern and Western imagery intertwine on the same granite, resembling a 17th-century globalized puzzle. Many visitors look for a "unique sight" in the center of the third level: a relief of the Virgin Mary stepping on a seven-headed dragon (or "seven-headed serpent"), accompanied by Chinese inscriptions symbolizing "Our Lady trampling the dragon." This fusion of imagery from the Book of Revelation with Eastern cultural elements is said to be influenced by Japanese Christian craftsmen and local artisans involved in the carving, making the visual language of the Ruins of St. Paul's particularly inclusive. Broadening your perspective, the Ruins of St. Paul's is not an isolated attraction. It is part of the "Historic Center of Macau," which includes over twenty historical buildings and was collectively listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. UNESCO's rationale is clear: this area fully demonstrates the long-term encounter, interaction, and coexistence of Chinese and Portuguese cultures. In other words, the Ruins of St. Paul's is not just a beautiful wall; it is a convergence point of city memory, trade routes, religion, science, and linguistic exchange. Behind the façade lies the "Museum of Sacred Art and Crypt," developed during restoration efforts in the 1990s. Archaeological and reinforcement work from 1990 to 1995 organized and displayed the underground foundations, crypt, and unearthed artifacts. In the cool crypt, you can see the religious orders and believers once sheltered by this church, making history tangible enough to converse with. For travelers who enjoy contrasts, don't miss the nearby Na Tcha Temple (built in 1888). On one side is the Portuguese church ruins, and on the other is a small Chinese temple, standing close together as if splitting "Macau" into two halves and reuniting them, telling two stories within the same line of sight. If you continue upward to Mount Fortress, overlooking the city rooftops and the sea, you'll better understand why religion, military, and trade were intertwined here. I particularly enjoy visiting in the early morning, when there are fewer tourists, allowing time to slowly study the carvings. The sea breeze pushes the clouds low, and light and shadow move across the stone surface like turning pages. Start from the lower level: the central arch is inscribed with "MATER DEI," flanked by the IHS emblem. Look up to see the figures of St. Ignatius and St. Francis Xavier, imagining their disciples crossing the seas to this city, learning Chinese, translating scriptures, and using this "visual catechism" to communicate with local communities. Then wander freely among the lions, chrysanthemums, and ships—you'll find that this wall is a microcosm of the Jesuits' missionary strategy: speaking in a language that can be understood. If you consider the Ruins of St. Paul's as a "stone book," it tells more than just religious stories. The college was one of East Asia's earliest Western-style higher education institutions, nurturing talents in fields ranging from linguistics to astronomy and geography. After the Jesuits were expelled by Portuguese authorities (1762), the college closed, and the fire reduced the building to the "pages" of the façade. Fortunately, the protection of world heritage and the city's awareness have kept this page from being closed. Practical tips: For photography, choose early morning or dusk, when the backlighting makes the stone carvings more three-dimensional. Don't just take photos from the front; move to the grassy slope on the left or the alley on the right for a more beautiful perspective of the façade. After viewing, you can visit Love Lane and Lou Kau Mansion before returning to Senado Square. To extend the historical narrative, include Mount Fortress and the museum in your itinerary to form a clearer outline of the "citadel" in your mind. If traveling with elders, the steps are not steep but still recommend resting a few times at the bottom before ascending; on rainy days, the steps can be slippery, so wear shoes with non-slip soles. As you leave and look back, the façade alternates between light and shadow behind the clouds. I often think of replacing the name "Ruins of St. Paul's" with a more humanized term: it is a gate that accommodates differences, allowing the distant to come in and the local to go out. Perhaps this is the true reason it has become a symbol of Macau—not just because it is beautiful, but because it reminds us that this city was born from encounters.Heinrich85883Macau's Xinmiao Supermarket Shipaiwan Store: Affordable Treasures in a High-Consumption Area

#September Good Places 2025 #cheap shopping #Macau When you come to Macau, many people will feel the high consumption here. Especially in tourist areas, prices are even higher. However, at the Shek Pai Wan store of Xin Miao Supermarket, You’ll find a shopping oasis in stark contrast to its surroundings. This supermarket is located in Shek Pai Wan, Macau. Surrounded by numerous high-end residences and high-consumption venues . But Xinmiao Supermarket always insists on providing cheap and varied goods. Become the first choice for local residents and savvy travelers. Excellent choice for cheap spending: In this high-consumption location in Taipa, The new seedling supermarket is undoubtedly the "stabilizer" of prices. Whether it’s daily necessities, fresh fruits and vegetables, or snacks and drinks. The prices here are very affordable. Let you buy all the items you need without spending a lot of money. The variety of goods is rich and diverse: There is a wide variety of goods in the supermarket. From local specialty foods to imported goods. You can find fresh meat, seafood, fruits and vegetables. You can also buy all kinds of snacks, drinks, and household items. Even some unique Macau souvenirs. Convenient transportation, convenient shopping: The Shek Pai Wan store has a superior location and convenient transportation. Tourists can easily reach it by public transportation. The supermarket has spacious space and clear planning of shopping routes. Make your shopping experience smoother and more enjoyable.星野Uim8Venetian Macau, Venice City Tour

#TravelTalk The Venetian Macao is Asia's largest entertainment and hotel complex. In addition to its hotel and casino, it also features a replica of Venice, Italy. There are gondola rides for sightseeing, and shopping opportunities are available. Highlights include the beautiful skyline, buildings, and bridges, offering numerous photo opportunities. Opening Hours: 10:00 AM - 10:00 PM. The hotel is open 24 hours. Admission: Free #Macau #thevenetianPchaพาเที่ยว5Macau Yiyantang desserts are a must-try for a refreshing summer treat 🤩

#Macau Food🌟 Macau dessert lovers must try! Yiyan Tang Dessert 🍧 📍Address: G/F, 1 Fulong New Street, New Road, Macau 🕰️Opening Hours: Noon to 11:00pm Yi Yan Candy Dessert is a must-have on Macau's food list! The restaurant is not very big, but the environment is chill, comfortable to sit, a group of friends gathering is great 😋 ~ The food is really of a standard! 🌈Food recommendation: 🍑 Mango Cha Fun ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ Creativity is bursting! This is my first time to eat mango + cha-fan in Macau. It's full of freshness ~ ice-cold taste + sweet but not greasy. It's super refreshing in summer. I sincerely recommend you to try it! 🙌🏻🫶🏻👍 🍔 Cheese Pork Chop Bun How can you not try authentic pork chop buns when you come to Macau? Crispy on the outside and tender on the inside, with crispy buns, it tastes layered, and there is a cheese thread effect, the taste is sooo good! 🥚 Portuguese egg tart/Bird's nest Portuguese tart Classic Portuguese Tart + Upgraded Bird's Nest Portuguese Tart is a popular choice, smooth and crispy, a must-try for dessert lovers! 🍉 Papaya stewed official swallow If you want to be healthy and tasty, this dessert can definitely be considered #Macau Food, let's make a date for a collection of Oatmeal Sweets Desserts! Take a wave of sweet check-in!魚皮食交8Macau is n

Macau is not just about Portuguese cuisine, recently a new experience - Vivienne Westwood Tea Set, is super surprising! I was not aware of the booking this time, because on a weekday, originally staying in the hotel wanted to try the restaurant and suddenly interior decoration, but found good things, whether the food, environment or service are satisfied, very high check-in, perfect for friends who like fashionable afternoon tea! Vivienne Westwood Tea Set (Macau Exclusive) Address: A luxury hotel in Macau (contact the hotel in advance for inquiries, it is recommended to book a reservation in advance ~) Opening hours: General afternoon tea (approx. 14:00-18:00), special arrangements are available on some days, please check with the hotel Price: Afternoon tea sets are usually around $300-$400 per person, depending on different combinations and number of people environment Featuring Vivienne Westwood’s classic elements, there are plenty of photo spots – British rock mix and elegance, spacious and beautiful space! But randomly photographed from an angle are super beautiful, with logo cutlery, simply perfect match, super like! After we sat down slowly more people entered the restaurant. Perfect for a gathering with girlfriends or a couple, the atmosphere is relaxed and spacious, especially suitable for celebrating small events or birthday gatherings! Signature dish Refreshments are elegantly shaped and sophisticated – Western muffins, mini sandwiches, seasonal desserts, each with Vivienne Westwood metal logo decoration or British ingenuity. Most appreciated each person a plate of 5 pieces of dessert, really each piece was very tasty, instead the signature macarons, not so crispy on the outside and soft on the inside, however with tea enjoy great. There are also a variety of coffees, specialty red tea, and flower and fruit teas. There are plenty of choices! service The service is excellent, the staff proactively introduces each afternoon tea, and the photography is helpful, so that you are not afraid of embarrassment in taking pictures. Friendly smile, very willing to proactively serve, flexible arrangements, details done, comfortable seating. Impressions after use Sincerely recommend! The taste is exquisite, with a traditional British flavor but adds a bit more creativity. The whole charter experience is very chill, playful and not too exaggerated. It's great for taking pictures and taking pictures. My friends have praised it. It's the best choice for afternoon tea in Macau. I originally wanted to try the oil-sealed duck leg Waffle, but after afternoon tea there was really no space. I'll come back next time! Practical tips If you plan to book a venue, remember to make a reservation with the hotel early. You don't have to wait for more people to compete with you! #Macau Afternoon Tea Recommendation #VivienneWestwoodTeaSet #Macau Charter Experience #Macau Beautiful Photography #English Style Afternoon Tea #Macau High Quality Restaurant_TI***ci7Must-See Guide for Night Tour in Macau

During my 48 hours in Macau, I felt like I had stepped into a dazzling movie scene🕶️! Every moment of my trip with my bestie was like it had a built-in filter, and the night views were stunningly beautiful~ 🏩Stay at a Legendary Hotel Our first stop was checking into the Grand Lisboa Hotel (Lisboa Avenue), where the floor-to-ceiling windows offered a panoramic view of the entire Macau Peninsula! The room was spacious enough to dance in, and the bedding was so comfortable it put me to sleep instantly💤 The biggest surprise was the infinity pool—every snap looked like an Instagram masterpiece~ It’s just a 10-minute walk to the famous Ruins of St. Paul’s, making the location absolutely perfect! 📸Taipa Island Adventure On the second day, we headed straight to Taipa Island (open all day), which is simply synonymous with luxury! Outside The Londoner Hotel, we saw a whole row of Rolls-Royces, and my bestie almost ran out of phone storage from all the photos🤳 I recommend visiting at dusk when the lights come on—the Venetian canals and the Parisian Tower are lit up, making the romance level skyrocket✨ 🥘Foodie Guide The buffet breakfast at the Grand Lisboa Hotel features amazing Portuguese egg tarts! Taipa’s Rua do Cunha is a food paradise—don’t miss the must-try sawdust pudding and pork chop buns. We tried three different places and still couldn’t get enough~ 💡Chloé’s Insider Tips: 1️⃣Taxis in Macau are quite expensive, but all major hotels offer free shuttle buses that are super convenient 2️⃣Reserve a whole day for Taipa Island, and don’t miss the Wynn Palace fountain show at 8 PM 3️⃣For photos, bring a little dress—you can easily snap magazine-cover-worthy shots in the hotel corridorsDelightful Harper_Lee144A-Ma Temple, a sacred World Heritage Site in Macau

#GetDiscountsWithoutLuck 🏯 Review of A-Ma Temple, Macau: A Sacred World Heritage Site 📜 History and Background A-Ma Temple, also known as the "Temple of the Goddess of Mercy" among Thais, is one of the oldest and most important temples in Macau. Built in 1488 during the Ming Dynasty, the temple's historical significance earned it a UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005, along with other sites in the Macau Historic Center. The name "Macau" itself originates from this temple. Originally, the area was called "A Ma Gao," which translates to "A Ma's Bay," later becoming the current "Macau." 🏮 Legend of Sacredness A-Ma Temple is steeped in legend about a young woman named Lin Ma (or Lin Mo) who was trying to cross to the Aomen Peninsula. During her journey, a severe storm sank several ships. Miraculously, only the ship Lin Ma was on survived. Upon reaching shore, she vanished. The villagers believed she was a sea goddess, descending to protect travelers, and built a temple in her honor. 🏛️ Architecture and Highlights A-Ma Temple blends Buddhist, Taoist, and folk beliefs. The temple complex comprises several important structures: Gate Pavilion - an intricately carved wooden door Memorial Arch - dedicated to the legend of the Goddess A-Ma Prayer Hall - used for religious ceremonies Hall of Benevolence - the oldest part, built in 1488 and housing a statue of the Goddess Mazu (A-Ma) Hall of Guanyin - housing a statue of the Goddess Guanyin Zhengjiao Chanlin - a Buddhist pavilion There is also a carved stone boat, believed to be the spot where the Goddess A-Ma first set foot on land. It is a place of great reverence for believers. 🙏 Prayers and Beliefs A-Ma Temple is renowned for its sacredness, particularly for prayers related to: Career - promotion and career advancement Finance - wealth, prosperity, and successful business Travel safety - especially sea travel Recommended prayer methods: Worship with incense, candles, and joss paper. Rub Thai banknotes without the number 4 on the carved boat-shaped stone in the temple. Pray for your desired blessings, such as financial, career, and business. Bring the money back to Thailand for merit-making, and it is believed that your wishes will be granted. 🗺️ Transportation A-Ma Temple is located in the southern part of Macau. It is very convenient to get there: By public bus: Take bus lines 1, 2, 5, 6B, 7, 10, 10A, 11, 18, 21A, 26, 28B, 55, MT4, or N3 and get off at the "A-Ma Temple" stop in front of the temple or the "Barra Square" stop opposite the temple. From the city center: Just 10-15 minutes by taxi or bus. ⏰ Opening Hours and Admission Fee Opening Hours: 7:00 AM - 6:00 PM daily (some sources state 8:00 AM - 6:00 PM) Admission: Free 💫 Summary A-Ma Temple is not only a sacred place of worship, but also an important cultural and historical site in Macau. A visit not only fulfills your faith, but also offers the opportunity to experience the beautiful art and architecture that reflects the perfect blend of Chinese and Portuguese cultures. It is a must-see for all visitors to Macau, especially those who are into spiritual practices. With its sacredness, solemn atmosphere, and rich history, A-Ma Temple has become one of Macau's most important symbols and a must-visit destination.AthaM7063-Day Macau Travel Itinerary

🏠Accommodation 1. San Tung Fong Commercial Inn South Wing Day 1 - Exploring the area near San Tung Fong Hotel - Take the casino shuttle buses: Casino Sand, Casino Lisboa, Casino Wynn - Ride the Macao LRT to the city ✅ - Purchase a Macao Pass at 7-Eleven (130 MOP, with a 25 MOP deposit refundable upon card return at Senado Square) ✅ - Visit Senado Square: Leo Cafe, Long Wa, Albergue 1601, Wong Chi Kei Noodles ✅, Sei Kee Cafe (Portuguese pork chop bun + milk tea), and try Portuguese cuisine - Pay respects to the waterfront Guan Yin statue, 700m walk ✅ - Explore Macau Fisherman's Wharf ✅ - Visit Tap Seac Square (bus stops: Pavilhao 2A, 7, 8, 8A, 9, 9A), 500m walk to St. Lazarus Church - Stroll along R. Nova a Guia - Take buses 2, 3A, 5, 10, 11, 21A, N3 to Kam Pek Community Centre - Try Lai Kei Sorvetes (opposite the Asics shoe store) Day 2 - Exploring the Venetian side - A-Ma Temple: Take bus 10 from Kam Pek to Templo A Ma ✅ - Macao Tower: Sai Van Lake, opposite Macao Tower - From Templo A Ma bus stop, take bus MT4 to Taipa, alight at Edf. Chun Leong ✅ - Visit Lord Stow's Bakery for the original egg tarts ✅ - Shop for affordable cosmetics at Cotai shopping malls - Explore Taipa Village ✅ - From bus stop T318 Chun Yuet Garden, visit Celeste-943 The Porte (coffee served in edible cups) ✅ - From Edf. Chun Leong bus stop, take bus 72 to Av. Cidade Nova/Venetian: Venetian (photo op at the Venetian footbridge) ✅ - Visit The Parisian Macao (Eiffel Tower) ✅ - Explore The Londoner Macao ✅ - Studio City - MGM Cotai - Wynn Palace - Macao Giant Panda Pavilion Day 3 - Near the accommodation (until 11 AM) - Have breakfast - Visit St. Paul's Ruins ✅ - Buy egg tarts to take home - From Praca Ponte Horta bus stop, take bus 26 to Aeroporto de Macau (35 minutes) - Taxi from the hotel to the airport (20 minutes)_FB***958Parisian Macao Travelogue: The Romantic Fantasy of the Las Vegas of the East

#September Good Places 2025 Macau, a city where China and the West meet, is famous for its bustling entertainment architecture in addition to its thick historical monuments. On the Golden Avenue in Cotai, **The Parisian Macao** stands in the sky with a replica of the Eiffel Tower, injecting romance and splendor into the land and becoming a landmark in the eyes of travelers. Stunning under the Eiffel Tower When new to Paris, the most eye-catching thing is the proportionally reduced Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower is spectacular during the day through the blue sky and white clouds, and after nightfall, it lights up the night sky with brilliant lights, complementing the surrounding Venetian and New Casino. Standing under the tower and looking up, you feel like you are in the streets of Paris across time and space in an instant. Visitors can climb the tower and overlook the bustling Golden Avenue and the sea view of the road. A reproduction of French style Walk into the lobby of the Parisian Hotel and you will be greeted by a dome and sculpture inspired by the Palace of Versailles. The splendid chandeliers, painted ceilings, and arcade shops create the splendor of a French court. The shopping avenue, which mimics the layout of the Champs-Élysées in Paris, is lined with boutiques and cafes, allowing people to immerse themselves in a European style while strolling. Here, you can not only enjoy the pleasure of shopping and entertainment, but also experience an imagination of "Paris of the East" through the architecture and atmosphere. The intertwining of entertainment and leisure As an integrated resort, Parisian Macao not only offers casino entertainment, but also a large theater, theme park and water world. During the day you can feel relaxed by the pool, while at night you can enjoy performances or participate in entertainment activities. This place satisfies the curiosity of tourists and brings a variety of experiences for family travel. Conclusion Parisian Macau, is a romantic fantasy. It is not the real Paris, but it creates the possibility of another kind of time and space through imitation and reproduction. When I gazed at the shining Eiffel Tower in the night, what loomed in my mind was not the distance between Paris and Macau, but the fantastic atmosphere where the two cities met here. Parisians embellish the bustling with romance, adding to the exotic atmosphere of Macau, the "Las Vegas of the East". It reminds travelers: Travel is not only about arriving in a distant place, but also about experiencing a different kind of landscape in imitation and fantasy.日本出發環球旅行者4Macau Museum Travelogue: A Scroll of History on the City Walls

#September2025 If the Ruins of St. Paul's is the symbol of Macau, then the Macao Museum (Museu de Macau), nestled atop the Mount Fortress, is a window into the city's soul. More than a mere display of artifacts, it weaves over 400 years of Macau's history, culture, and life into a vivid tapestry through images, artifacts, and space. Amidst the Ancient Fortress, the Beginning of the Museum The Macao Museum is built atop the Mount Fortress. Originally a 17th-century military fortress, the Fortress served to protect St. Paul's Church and the entire city of Macau. Walking along the stone paths, ancient cannons still stand, and from the ramparts, one can gaze upon the dazzling golden lights of the Grand Lisboa Hotel. The interweaving of past and present echoes the museum's spirit: the coexistence of history and modernity. Exhibition Hall Tour: A Symphony of Eastern and Western Cultures The exhibition is divided into three sections: • The first section showcases Macau's early history. From fishing village utensils to scenes of initial interaction between China and Portugal, it illustrates the city's rise from a small port to the global stage. • The second section showcases the interplay of Chinese and Western cultures. From Portuguese blue-flowered porcelain fragments to Chinese ritual vessels and church icons, all demonstrate Macau's uniqueness as a cultural crossroads. • The third section focuses on modern society. Newspapers, vintage photographs, the evolution of the entertainment industry, and even the legacy of handicrafts all offer a glimpse into a truly multifaceted Macau. Here, history isn't an abstract era but a tangible memory: a wood carving, a barcarolle, an old map, all transport visitors back in time. Quiet Contemplation and Reflection Compared to the bustling Ruins of St. Paul's, the Macau Museum is remarkably tranquil. Wandering through the exhibition halls feels like conversing with an elderly man, listening to his stories. As we ascend to the rooftop garden, gazing out over the panoramic view of Macau, a profound feeling arises: the city's prosperity and contradictions, its East and West, are all reflected in the landscape before us and the land beneath our feet. Conclusion The Macau Museum is more than just a place for cultural preservation; it serves as a mirror, reflecting Macau's diverse identities and historical memories. When I left, the setting sun was shining on the walls of Macau Fortress, and the golden light and the ancient bricks reflected each other. At that moment, I knew that if I wanted to truly understand Macau, I couldn’t just look at the neon lights and prosperity, but I also needed to walk into this museum and have a dialogue with Macau deep in time.日本出發環球旅行者4Macau Travelogue: The Civilization on the Weathered Stone Wall

Macau, a city where Eastern and Western cultures intertwine, is renowned for its dazzling casino lights and ancient cobblestone streets. Yet, beyond the bustling glamour, the **Ruins of St. Paul’s** remain a must-visit landmark for travelers. It is not only a symbol of Macau but also a historical imprint left by the collision of Eastern and Western civilizations. Stone Steps and Majestic Facade As you ascend through narrow alleys, your gaze is gradually drawn to the towering stone wall. Built in the 1620s, the St. Paul’s Church was once grand and imposing but was destroyed by a fire in 1835, leaving only its front facade and some stone steps. The facade is divided into five levels, intricately carved: the Virgin Mary and Child above, grapevines, lotus flowers, and flying dragons below—images blending Eastern and Western elements. Each detail carries profound meaning, symbolizing Catholic faith while incorporating Eastern cultural motifs. Standing on the steps and looking up, one can almost feel the grandeur and poignancy of history. A Testament to East-West Interactions The Ruins of St. Paul’s are not merely remnants of a religious building but a "stone-carved history book." They bear witness to the interactions between Portuguese colonizers and Chinese society in the 17th century, reflecting Macau’s unique role as a "bridge of Eastern and Western cultures." In the reliefs, Western saints coexist with Eastern mythical creatures, symbolizing cultural intersection and fusion. This visual language makes the Ruins of St. Paul’s a representation of coexistence between civilizations, rather than merely a colonial relic. Crowds and Contemplation Today, the Ruins of St. Paul’s are bustling with visitors. During the day, the steps are filled with tourists taking photos; at night, under the illumination, the stone wall appears even more solemn. However, visiting in the early morning or late at night, when the steps return to tranquility and the breeze brushes through the stone crevices, the silence of history emerges. At that moment, standing before the Ruins of St. Paul’s is not just about viewing a relic but engaging in a dialogue with four centuries of time. Conclusion The Ruins of St. Paul’s are not only a tourist icon of Macau but also a parable of civilization. With its weathered walls, it reminds us of the fleeting nature of glory while proving that cultural exchange can leave an eternal mark. As I descended the stone steps and turned back to gaze at the weathered stone wall, I felt not only the sentiment of the journey but also a deep reverence for history. The Ruins of St. Paul’s are not just a landmark of Macau but an everlasting symphony of Eastern and Western civilizations.日本出發環球旅行者4Macau Fisherman's Wharf Travelogue: A Harbor Dream in an Exotic Landscape

#September2025 Macau, often known as the "Las Vegas of the East," often draws visitors with its dazzling casino lights. However, Fisherman's Wharf, located in the newly reclaimed Outer Harbor area, adds a distinct dimension to the city. It's a leisure and entertainment complex, and its rich, exotic architectural style creates a dreamlike travel experience. European Charm and Classical Imagination Entering Fisherman's Wharf is like stepping into a miniature European world. The ancient Roman Colosseum looms before you, its mottled stone walls and arches transporting you back thousands of years to the classical era. On the other side, the Venetian canals and Southern European architecture, set against a blue sky and white clouds, create the illusion of being transported to the Mediterranean coast. This isn't just a replica of architecture; it's a collage of cultures. From ancient Egyptian columns to medieval European streets, Fisherman's Wharf's dramatic spatial layout cleverly interweaves history and fantasy. A Fusion of Entertainment and Recreation Fisherman's Wharf is more than just an architectural showcase; it's a leisure park integrating entertainment, shopping, and dining. Stroll through the antique-style streets and explore the exotic cuisine of cafés and specialty restaurants. At night, the illuminated Roman Colosseum and the waterfront create a vibrant atmosphere of romance. For panoramic sea views, the wooden promenade overlooking the water is the perfect spot. When the crowds are sparse, the only sounds are the crashing of waves and the rustling of footsteps, offering a moment of tranquility amidst the bustling city of Macau. A Blend of History and Modernity Since its opening in 2006, Fisherman's Wharf has undergone a period of decline and subsequent renovations. While it lacks the rich history of the Ruins of St. Paul's or the excitement of a casino, it reflects Macau's unique identity as a crossroads of Eastern and Western cultures through a playful, exotic imagination. For travelers, this is a perfect photo spot; for the city, Fisherman's Wharf symbolizes a modern cultural landscape—neither a purely historical heritage nor a single commercial building, but rather a spatial experiment within the context of a "tourist city." Conclusion As I left Fisherman's Wharf, I looked back at the amphitheater, which seemed to have been transplanted from ancient Rome, and a sense of detachment struck me: this city always manages to construct illusions between reality and imagination. Macau Fisherman's Wharf is not only a place for sightseeing and leisure, but also a microcosm of how modern cities interpret history and collage culture.日本出發環球旅行者4

Popular Macau topics

2025 Recommended Guides in Macau (Updated October)

11556 posts

2025 Recommended Attraction in Macau (Updated October)

8843 posts

2025 Recommended Restaurant in Macau (Updated October)

6326 posts

Destinations related to Macau

2025 Hong Kong Travel Guide: Must-see attractions, popular food, hotels, transportation routes (updated in October)

95355 posts

2025 Zhuhai Travel Guide: Must-see attractions, popular food, hotels, transportation routes (updated in October)

5885 posts

2025 Jiangmen Travel Guide: Must-see attractions, popular food, hotels, transportation routes (updated in October)

593 posts

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 100

Post

More recommendations

Popular Trip Moments

Where Art is Gilded and Air Dazzles: The Interior World of MGM Macau | The Garden’s Lantern-Lit Breath | The Nocturnal Tides of Sanmalo | The Canvas of Velocity: Where Art and Hypercars Collide | A Different Kind of Crown on the Cotai Strip | The Neon Nexus of the East | Wynn Palace Macau | Macau~ You don’t have to enter casinos to have an amazing time! | Check in at Lou Lim Ieoc Park to enjoy the lanterns | ✨🇲🇴The perfect flat white discovered at Curve Coffee, a hidden cafe in a Macau alley! | Recommended Chill Family Attractions in Macau 🧒🏻👧🏻 | Macau's Mystique✨ | Churchill Restaurant Macau | 🇲🇴Macau Restaurant Exploration | What are my options for skipping hotel breakfast? 🧐🤔 | Weekend Getaway at The Londoner Hotel in Macau | Andaz Macau Hotel with Full Glass Views | Little Venice Indoor feels like Outdoor! | Macau Fisherman's Wharf offers a European vibe. | Performance Lake | When the Sky Blooms in Temporary Gardens | A Luminous Tapestry Woven in Light | Where Lanterns Dance with Stained Glass | Where Pavé Meets Pavement: A Confluence of Hypercar and Horological Art | Macau Fisherman's Wharf | Macao Museum | Grand Lisboa Casino | [Macau Peninsula] Stunning night view spots🌃📸 | Breaking into the Iceland of Wenling! The secret black sand beach is absolutely stunning | 🇲🇴 Allow yourself to experience the romance of a hotel: The Parisian Champagne Suite | Macau Dining Guide | Newly Opened High-Quality Western Restaurant at Galaxy Macau

Recommended Attractions at Popular Destinations

Popular Attractions in Kyoto | Popular Attractions in Sydney | Popular Attractions in Tokyo | Popular Attractions in Chefchaouene | Popular Attractions in Bali | Popular Attractions in Walt Disney World Resort | Popular Attractions in Paris | Popular Attractions in Melbourne | Popular Attractions in Bangkok | Popular Attractions in Zanzibar Island | Popular Attractions in Osaka | Popular Attractions in Iguazu National Park(Argentina) | Popular Attractions in Kuala Lumpur | Popular Attractions in Dubai | Popular Attractions in Singapore | Popular Attractions in Shanghai | Popular Attractions in Rome | Popular Attractions in Los Angeles | Popular Attractions in Las Vegas | Popular Attractions in Phuket | Popular Attractions in New York | Popular Attractions in Barcelona | Popular Attractions in Beijing | Popular Attractions in West Lake | Popular Attractions in London | Popular Attractions in Florence | Popular Attractions in Chengdu | Popular Attractions in Madrid | Popular Attractions in Istanbul | Popular Attractions in Jungfrau Region

Popular Restaurants in Macau

Five Foot Road(MGM COTAI) | Yee Shun Milk Company | Luk Kee Noodle | WONG CHI KEI | Chan Seng Kei | Macau Ming Kee Beef food | IMPERIAL COURT(MGM MACAU) | Lai Heen | Pearl Dragon | Mok Yi Kei | DUMBO RESTAURANTE | The Eight | Loja Sopa De Fita Cheong Kei | ROBUCHON AU DÔME | Chan Kwong Kei BBQ Shop | Loja de Doces Hang Heong Un | Talay Thai Restaurant | Mesa by José Avillez | Emperor Court | SW Steakhouse | CHÚN(MGM COTAI) | Churchill's Table | Cafe e Nata Margaret's | Restaurante Fernando | Nam Ping | Sing Lei Cha Chaan Teng | Jade Dragon | Palace Garden | Chiado | Wing Lei

Popular Ranked Lists

Popular Trending Attractions in Takayama | Top 50 Luxury Hotels near Innsbruck | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Auckland | Popular Trending Attractions in Yongji | Top 10 Luxury Hotels near Bac Giang | Popular Premium Hotels in Vallromanes | Top 10 Local Restaurants in Lushan Global Geopark | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Berlin | Popular Trending Attractions in Anji | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Xi'an | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Changsha | Popular Premium Hotels in Arrowtown | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Nanjing | Popular Trending Attractions in Dali | Popular Premium Hotels in Pokolbin | Popular Premium Hotels in Whitianga | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Bruges | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Florence | Top 50 Luxury Hotels near Monza | Popular Premium Hotels in La Guaira State | Popular Premium Hotels in Floriana | Popular Premium Hotels in Puerto Varas | Top 10 Trending Attractions in Changchun | Top 10 Trending Attractions in Shenzhen | Popular Trending Attractions in Hefei | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Sapporo | Top 50 Must-Visit Restaurants in Shenzhen | Popular Trending Attractions in Bali | Top 10 Trending Attractions in Dubai | Popular Premium Hotels in Gwynedd

About

Payment methods

Our partners

Copyright © 2025 Trip.com Travel Singapore Pte. Ltd. All rights reserved

Site Operator: Trip.com Travel Singapore Pte. Ltd.

Site Operator: Trip.com Travel Singapore Pte. Ltd.